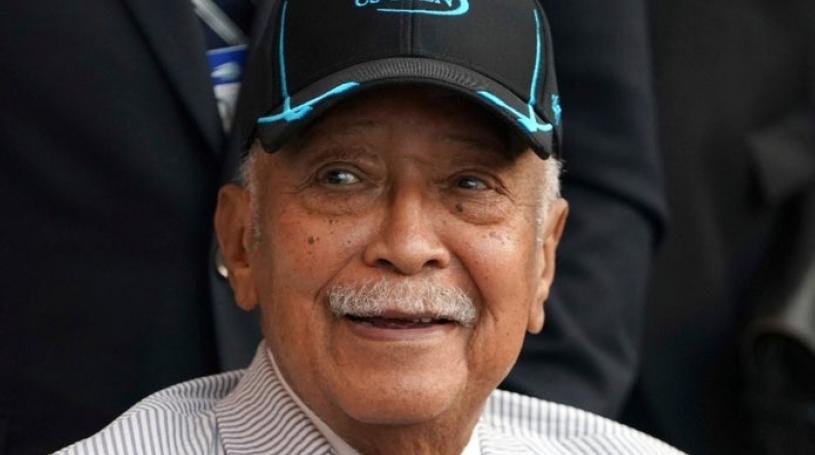

David Dinkins Dies At 93; Was New York City Mayor In Early 1990s

NEW YORK, NY — He was born in New Jersey but made his name in New York City, which he loved and led. David Dinkins, who became — and remains — New York City's only Black mayor, died Monday. He was 93.

Dinkins was found unconscious around 9 p.m. by a home health aide who called 911, two city officials told Patch. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

After serving with the Marines in Korea, Dinkins settled in Harlem and became a lawyer. He soon became involved in local Democratic politics. He was elected to the state Assembly in 1966. He also served as city clerk and president of the Board of Elections before being elected Manhattan borough president in 1985.

Four years later, he was elected as the city's 106th mayor, defeating Rudolph Giuliani by a mere 47,000 votes.

To get there, Dinkins first defeated Ed Koch in the primary. Koch had been seeking a fourth term but saw his hopes dashed by Dinkins, who was able to take advantage of a storm of problems that enveloped the Koch administration including racial violence and a corruption scandal.

Giuliani, who defeated Dinkins in 1993, tweeted Monday night that Dinkins "gave a great deal of his life in service to our great city. That service is respected and honored by all."

Dinkins was a quiet, deliberate man, a counterpoint to Koch.

His campaign for mayor was built around promises of trying to unify the city, to be a mayor for all New Yorkers, to lead the city that he often referred to as a "gorgeous mosaic."

It would not be easy. He inherited a city with large financial problems that forced Dinkins to raise taxes and cut services. It also made it hard to combat a crack-driven crime wave. Dinkins' first police commissioner, Lee Brown, would be ousted before Dinkins left office as crime continued to rise.

A sign that racial tensions were not going anywhere arrived in his first year in office when Black residents started around-the-clock protests of a Korean grocery. Dinkins would later regret not having quickly stepped in to end the boycott.

Things took a bad turn for the city and Dinkins in August 1991. when a driver in the motorcade of Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, the leader of the Lubavitcher Jews, struck and killed Gavin Cato, an 8-year-old Black child.

The incident led to four days of rioting that saw a Jewish student from Australia, Yankel Rosenbaum, killed by an angry mob.

Dinkins was heavily criticized for not acting quickly enough to stop the riots. A state report found major faults with how the city responded.

In the aftermath, Dinkins hired Ray Kelly to replace Brown — and, over the next two years, the city saw crime start to drop dramatically, beginning a trend for which Giuliani would later claim credit.

There would be several accomplishments during his time in office including welcoming Nelson Mandela after the South African's release following decades in prison, and a major deal with the United States Tennis Association to keep the U.S. Open in New York.

The drop in crime and the other accomplishments would not be enough to save the Dinkins administration, and Giuliani would win their rematch.

After leaving office, Dinkins went on to teach at Columbia University, remained active in city affairs, and eventually grew into the role of elder statesman. When the city under Giuliani settled with the Rosenbaum family, Dinkins reached out to his successor and invited him for dinner.

Giuliani refused.

In October, Joyce — the love of Dinkins' life, the woman to whom he was married for more than 60 years — died. Dinkins was left distraught by the loss.